For thousands of years, farmers have used genetic diversity to cope with weather variability and changing climate conditions. They have stored, planted, selected and improved seeds to continue producing food in a dynamic environment.

Community seed banks are mostly informal collections of seeds maintained by local communities and managed with their traditional knowledge, whose primary function is to conserve seeds for local use. They can play a major role in climate change adaptation, according to a recent article published by Bioversity International’s researchers Ronnie Vernooy, Bhuwon Sthapit, Gloria Otieno, Pitambar Shrestha and Arnab Gupta.

Based on various countries’ experiences, the article argues that, ‘community seed banks can enhance the resilience of farmers’ by securing ‘access to, and availability of, diverse, locally adapted crops and varieties’.

According to Ronnie Vernooy, genetic resources policy specialist at Bioversity International, ‘mostly because of climate change, there’s a stronger interest in establishing and supporting community seed banks’. However, many of them ‘are still quite fragile, organizationally and in terms of technical management’, he added.

Bioversity International, which is working in several countries on informal seed systems, has designed a project for community seedbanks Platform and is currently looking for donors interested in its implementation. The Platform aims at reinforcing farmers’ seed systems by supporting existing community seed banks as well as national or regional community seedbank networks around the world, scaling out their activities and contributing to their sustainability. It should have four key functions, covering documentation and analysis to practical experiences, capacity building, research agenda coordination and digitalization andmanagement of data.

But why do community seed banks matter?

Tools for adaptation

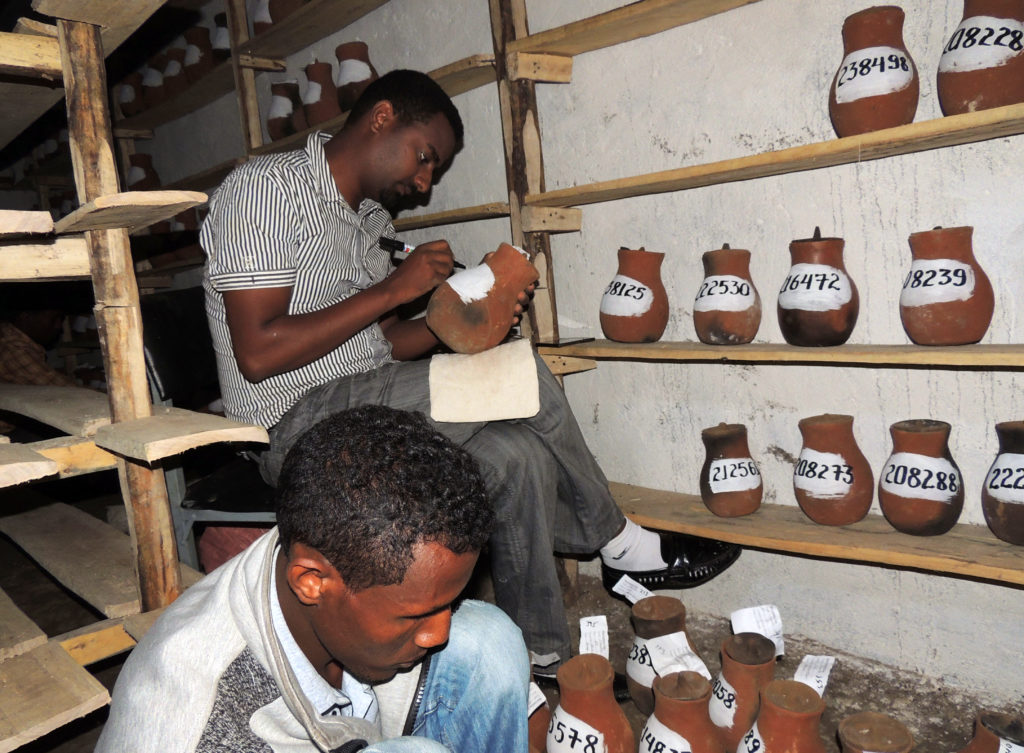

Seeds are stored in diverse types of collections, ranging from international and national genebanks, or ex situ collections where seeds remain often for years or decades, to small seed banks managed locally by farmers. ‘In the ex-situ collections … seeds are like frozen in time … That means there’s no chance [for them] to adapt in the field to changing conditions’, Ronnie Vernooy, explained to Degrees of Latitude.

In community banks, seeds usually remain for shorter terms, ‘ sometimes for one year’, Vernooy specified, to be then distributed to farmers: ‘Those plants are in the field and in the real conditions, so they are adapting themselves to changing circumstances. Then farmers usually select the best seeds of any given crop in the field. Part of those seeds goes back to the community seed banks and the next year the cycle continues’. Moreover, genebanks focus more on the major food crops, while community banks tend to conserve all the diversity farmers have on field, including minor crops, neglected varieties, medicinal plants, wild relatives and even trees.

Community banks not only conserve genetic diversity, they ‘have the potential … to become seed producers and it’s happening … but it requires support’, Vernooy said. Compared to the formal seed sector – which includes research institutions, genebanks, governmental bodies and private companies – the informal seed bank offers several advantages to small farmers, according to Vernooy. It provides not only ‘broader [genetic] diversity’, but seeds that are better adapted to farming systems that ‘tend to be diverse, [located] in marginal, very dry or mountainous areas, etc.’, he explained. ‘[Seeds from the formal sector] tend to require high level of inputs – fertilizers, chemical fertilizers, pesticides, herbicides … – and the price is often high’.

However, ‘it’s not a black and white system’, he stressed. The formal sector can help building farmers’ capacities. In fact, ‘in many countries we are trying to breach the gap between the formal and the informal systems with activities like participatory plant breeding, but also with the community seed banks … We try to bring the national genebanks work together with the community seed banks’, he said. In an ‘ideal world community seed banks could be part of what’s called a national conservation system. Right now, governments channel money into national genebanks … Our argument is why not also put a small amount of money into each of the community seed banks that exists or into the new ones that can be established?’, Vernooy said.

An enabling legal environment

Strengthening community seed banks requires not only technical and financial support but also an enabling policy and legal environment. In many countries, apart from a few like Bhutan, Nepal, Uganda, South Africa, Brazil, “there is no or little recognition of and support for community seed banks …, [and] farmers are not allowed to sell farm-saved seed. In others, legislation to protect farmers’ genetic resources is lacking’, Vernooy’s article reports.

Laws and regulations that can conflict ‘on what community seed banks are trying to do, [for instance] the intellectual property rights policies …’ are also often in place, Vernooy explained. Community seed banks are ‘like collective enterprises’ managed cooperatively: ‘Laws that prohibit or restrain these collective uses are in contradiction to what community seeds banks do’, Vernooy explained.

From an international perspective, the Convention of Biological Diversity and the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture have been ‘quite supporting’, according to Vernooy. A study out of the Norwegian Development Fund, suggests that community seed banks can also contribute to the implementation of farmers’ rights to save, use, exchange and sell farm-saved seeds. Those rights are recognized by ITPGRFA, which is legally-binding for 143 countries. The Treaty demands contracting parties not only to promote or support ‘farmers and local communities’ efforts to manage and conserve on-farm their plant genetic resources for food and agriculture’ but also ‘in situ conservation of wild crop relatives and wild plants for food production’.

‘ITPGRFA has the farmers’ rights and in principle the text is very much in support of community seed banks, but then it goes back to the national governments to implement those international agreements. So, we are back to the same situation’, Vernooy said.

However, the direction seems clear: ‘There’s quite a strong international movement of people working on these issues and the international treaty itself is quite interested in advancing on this’, he said.

Photo credits: Bioversity International – Bioversity International/C.Fadda – Seeds for Needs, Ethiopia